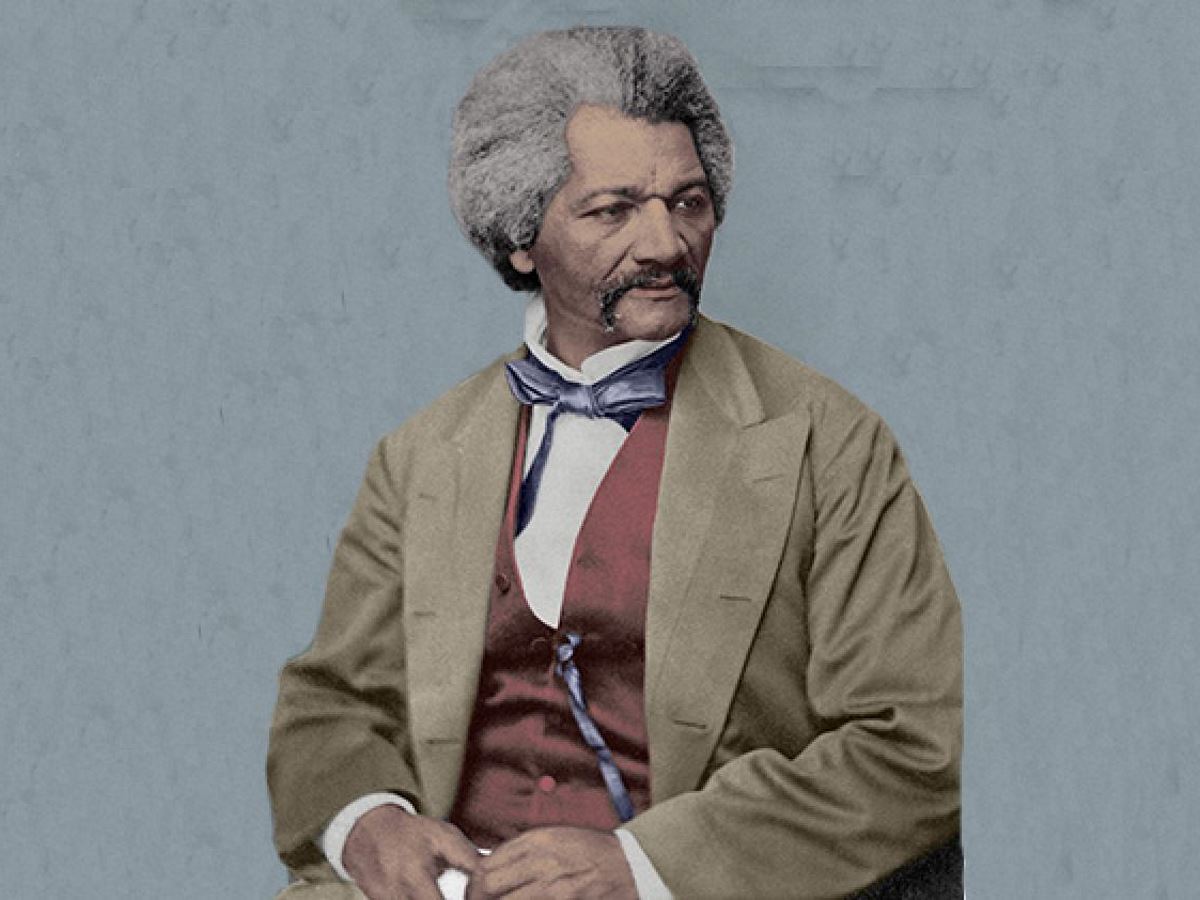

Some time in 1817, somewhere in Talbot County on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Harriet Bailey gave birth to a baby boy. She named him Frederick. She did not get to raise him. Shortly after her son’s birth Harriet was sent to work on a farm 12 miles away. Harriet, you see, was a slave. Her son was only to see her four or five times before her death seven years later. These visits are described in the opening paragraphs of the Narrative Life of Frederick Douglas:

I never saw my mother to know her as such more than four or five times in my life; and each of these times was short in duration and at night…She made her journeys to see me in the night, travelling the whole distance on foot, after the performance of her day’s work…I do not recollect ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.*

I have read this passage a hundred times or more, and cannot read it without weeping – sometimes violently. I think of that poor woman, torn from her son, planning for months to steal away in the night, walking twelve miles each way just to lay down with him a few hours, risking a beating or death if she was caught – and it is more than I can bear.

And yet the man who owned her doubtlessly thought of himself as a good Christian. He certainly listened to his parson use the scriptures to tell him so every Sunday. I thought of Harriet Bailey and of her owner after I overheard some brethren talking a while back about race, the Stars-and-Bars, and this and that. One said, “I’m sure slavery was not nearly as bad as the history books tell it,” as the others nodded agreement.

I’ve waited awhile to formulate a response. My impulse was to use history and the scriptures to demonstrate that the Roman institution of slavery the Bible addresses and the institution practiced in the United States are completely different, and thus the American version of slavery is indefensible. This is completely true, the argument easily made - but there is a bigger truth we need to address.

The truth is personal, not theoretical. If a value is not personal – not tied to life as persons live it – it is not true. “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath,” Jesus declares in Mark 2.27. He uses a personal example – David eating the consecrated bread - to apply this truth. When Paul is asked to deal with the topic of slavery (see the book of Philemon) he makes arguments that are true and completely personal. When Jesus prosecutes the scribes and Pharisees in Matthew 23, He consistently accuses them of ignoring the personal nature of truth. The Pharisees had fine theories of how to keep and protect the law, but in actuality they robbed widow’s houses, and killed the prophets.

Truth is personal. Truth emanates from a Person (God: see Psalm 119.160), is expressed through a person (Jesus: see John 1.17), and is given for persons (us: see John 8.32). Moral truth is not mathematical, theoretical, or abstract – it is absolutely and irrevocably tied to the lives humans live. Thus, when we think about the tough issues we must keep our consideration personal if we are ever to arrive at the truth – we must use the Bible to know the person of God, to follow the person of Jesus, and to apply what we have learned to the actual lives persons live.

One could respond to slavery’s proponents, past and present, by arguing abstract truth, OR one could remember Harriet Bailey, and then ask:

“Explain how treating a person this way is following Jesus?”

An interlocutor could supply a well argued, lawyerly answer to the abstract argument. But no one can come up with a satisfactory answer to the personal one.

- Barry Bryson

*Narrative Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, first published in 1845 at the Anti-Slavery office, Boston MA.